If you’re a marketer looking to send the right ad to the right person in the right place, programmatically buying online video ads on the open exchange is a monumentally stupid move. If you’re a brand trying to advertise that way, you’re wasting much, if not most, of your ad budget. If you’re an agency doing this, you’re doing things the easy way rather than the right way. You’re wasting your clients’ money, and it will lead to your eventual termination.

It’s been common knowledge in the less-traveled sectors of the digital advertising world that open exchange video inventory has a huge percentage of crap in it. Yet media buyers and traders transact on it anyway, either due to laziness, ignorance, or both.

I am here today to relieve you of your ignorance. Buying online video ads on the open exchanges is a bad idea for three reasons:

- Most of the video inventory available, in my experience, is re-purposed 300×250 display banners set up to run video ads–also known as “in-banner video” (or IBV).

- What’s not in-banner video is often arbitraged VAST video, which is of very poor quality.

- If you’re buying video on the open exchange, it’s much more likely to be botnet/fraudulent inventory than if you set up a programmatic deal with a publisher.

In our travels along the information superhighway, I think we’ve all seen in-banner video–video playing in an ad slot ordinarily intended for a display banner.

These video units almost never have any good content playing–the content itself is too small to see, and the production values are non-existent. The only point of having these units is to make them available for advertising.

In-Banner Video is a Bad Ad Experience

In-banner video ads are horrible for a number of reasons–they are slow to load, they’re data intensive, they decimate a smartphone’s battery power (a phone can lose 10% of its power from one crappy IBV ad). But for our purposes, IBV is a terrible advertising experience because the ads themselves are so small.

Legitimate VAST video ads are shaped like TV ads, which have aspect ratios of 16:9 (1.777:1) or 4:3 (1.333:1). Typically, the banners that run in-banner are 300×250 banners, which have an aspect ratio of (1.2:1)–which means that if you fit an entire VAST video ad in a 300×250 slot, the ad itself looks warped.

Most advertisers know this. A still-relevant AdExchanger 2015 piece claims in-banner video doesn’t drive ROI as well as standard-sized video, and in-stream video is ultimately gets more engagement. This matches my own experience.

So how do these in-banner videos wind up being available for purchase and in ecosystem in the first place?

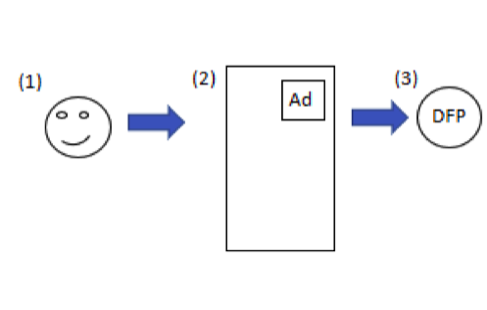

A Normal Display Ad Serving Environment

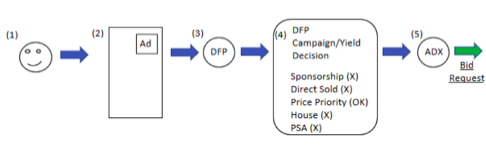

In a normal ad serving environment, a person visits a webpage or mobile app (1). The webpage has a slot for an advertisement (2), which serves ads through a JavaScript tag from Doubleclick for Publishers (or DFP), the world’s most popular ad server (3). Because the website owner wants to monetize this inventory, they place a banner ad slot on their page, which fires as the page loads.

DFP looks at the campaigns the publisher has to deliver (4). There aren’t any sponsorships or direct sold campaigns, so they’re running a “Price Priority” tag, which essentially tells the ad server, “Run what will make us the most money.” In this case, the ad server runs a JavaScript video tag from Google AdX (5), which is a very popular supply side platform (or SSP). The SSP sends out a bid request, i.e. the start of an auction, asking a bunch of demand side platforms (or DSPs) to bid if they want to serve an impression.

The DSPs send back bid responses (6) in an attempt to win that impression. The winner of the impression, DSP1, bids $1.50 CPM; but since the second-highest bid was only $1 CPM, the amount the buyer will pay is $1.01 as RTB is a Dutch auction model.

The user of the DSP1 seat is serving a JavaScript display tag from DCM, or DoubleClick Creative Manager, also a Google product and the world’s most popular third-party creative server. Within DCM is a raw .gif, .jpg or .png file, which is trafficked in DCM by the media buying agency and sent to the publisher. The agency was hired by the brand to buy digital media—to reach the right customers in the right place at the right time, and drive that customer to increase sales.

So, if you’re keeping track, the ad travels from DCM to DSP1 to ADX to DFP to the publisher’s page and website visitor. This is a fairly typical programmatic display execution and the way most people think their display spend is happening. It’s also the mechanism behind how in-banner video works.

The In-Banner Video Ad Serving Environment

Now, the process for an IBV creative is the same until we get to the DSP. An in-banner video buyer will traffic the in-banner video JavaScript tag into the ad server of the DSP, and target the campaign to a well-known website or mobile application (think Espn.com, Yahoo.com, or a mobile gaming app). Once they win that display impression, they run that in-banner video JavaScript tag.

The in-banner video JavaScript tag is a self-contained unit that holds all of the things a publisher needs to run a video ad. All through a piece of code, the in-banner video unit plays video files, hosts and serves third-party ad tags, and has a yield management/ad mediation system where you select to run more of some types of ad and fewer of less. Plus it serves actual video content.

Long story short: Using in-banner video technology, a display banner is transmogrified into a VAST, pre-roll video unit that’s ready to be monetized just like any other; and the IBV ad server does yield management, or “price priority” campaigns, just like DFP does.

So the new video ad unit is created and is again put out to the DSPs. This time, since it’s a video impression, and mostly video DSP buyers are interested. Potentially DSP2 wins the impression and serves a video creative in a 300×250 ad slot, which was sent to them by a Big Six agency on behalf of a brand.

Now, it would be one thing if the arbitrageur created only one pre-roll ad slot per display impression purchased. However, in actuality, dozens of pre-roll ad slots are created during this process.

In-Banner Video Creates Lots of New Ad Slots

Here’s what actually goes down when an IBV JavaScript tag is called:

Step 1: Call IBV JS tag.

Step 2: Start up yield management/monetization waterfall.

Step 3: Call SSP tag. Does SSP have an ad? If so, run the ad. If not, go to the next partner.

Step 4-lots: Call next monetization partner. Does the next partner have an ad? Keep this going on and on until you either find a partner that wants to buy and ad, or you run out of partners.

Last Step: Once you run out of partners, go back to Step 2, and start this all over again.

All of this waterfalling happens in hundredths of a second, and through this process, dozens, if not hundreds, of new VAST video impressions are created.

These new ad slots almost all have low price floors, and remember, because the IBV buyer is targeting well-known sites like yahoo.com or espn.com, it looks like a high-quality video ad! That makes them prime targets to be purchased through programmatic video buying by a legitimate marketer. I’ve heard of stories where 1,000 impressions are bought through the DSP, which creates 100,000 video ad calls in the various exchanges. Even if a tiny fraction of these ads get bought, the IBV buyer makes his money on the sale of a newly-created impression.

And the ads do get purchased. In 2015, DoubleVerify data showed that nearly 50% of video ads bought programmatically are served in-banner, and increasingly autoplay with the sound off. That trend doesn’t appear to have abated, at least in my experience.

In-banner video isn’t the only reason why video buyers should stay off the open exchange. “One weird trick” called VAST arbitrage makes open exchange video ads more expensive and less effective.

VAST Arbitraged Ads on the Open Exchange

Standard display ads are sent through JavaScript and load in a webpage or app, similar to how other page elements are loaded. JavaScript is a programming language. VAST, [on the other hand, is a video ad serving template (hence the acronym) created by the IAB, a “universal XML schema for serving ads to digital video players, and describes expected video player behavior when executing VAST formatted ad responses.”

So they’re pretty clearly different technical beasts, even though both are used to serve digital ads.

VAST ads are much more complicated and have a lot more moving parts where things could go wrong. This doesn’t take an ad-tech genius to figure out, but if you dealt with VAST ads before, you know of many situations where things can go wrong (see pages 54-55 of the IAB’s template for some reasons).

Because of this extra complication, video buyers and sellers in the marketplace came to a compromise. If for some reason or another a video ad doesn’t play when it’s supposed to, it’s taken like a mulligan on both sides, meaning that the seller (publisher) doesn’t get paid for that ad slot, and the buyer (agency or DSP) doesn’t have to pay for an ad slot they didn’t use.

So if I’m a marketer, and I want to run a VAST video ad on Espn.com, and something goes wrong–either too many redirects, or a timeout, or something doesn’t work–I don’t have to pay ESPN for that ad… but ESPN loses an opportunity to fill an ad slot, which costs them money.

Here’s where it gets interesting: VAST arbitrageurs use this quirk to their advantage to create a risk-free arbitrage environment where there is literally no downside to the buyer, and where it’s impossible not to make money. How is it done?

How VAST Arbitrage Happens

Remember the normal way a video ad is served. With VAST arbitrage, the process is the same, up until the DSP wins an ad slot. Instead of running a normal creative that has a raw media file attached, they put in another SSP tag. Another bid request gets sent out, with a few caveats. First is that the arbitrageur puts in a high bid floor. I select $10 here, to ensure the re-sold impression turns a profit.

At this point, either someone buys the re-sold impression… or they don’t. If they don’t, which is what occurs the vast majority of the time (no pun intended), there’s no ad to call and the SSP throws a VAST error. Due to the way VAST video ads are bought and sold, the seller loses an opportunity to monetize an ad slot and the buyer loses an opportunity to fill an ad. If someone does buy the resold ad slot, the process then finishes up the same way the traditional video buying occurs.

To reiterate, if you buy a video impression with the intention to resell it at the exact same time, and you’re able to resell it for more you paid initially, you’re guaranteed to make money. And if for some reason you’re not able to resell it, the ad registers an error, and you’re not on the hook to pay anything! Pretty great, right?

If you have 1 million opportunities to resell an ad, and you only manage to do it 1% of the time, you’re still making some profit. If you can extend that to 1 million per day, you’re making big profits! All of this makes video ad serving an almost perfect arbitrage environment.

In normal advertising campaigns, the error rate on impressions is very low—below 5%. But in arbitrage campaigns, error rates can run 95% or higher, which leads to a lot of lost revenue potential for publishers.

Now, I might be making VAST arbitrage look easier than it actually is. Because this is such an easy/dumb way to make money, there are a lot of people doing it, all trying to bid on the same impressions. And everyone bidding on these same impressions is trying to resell ads to a fixed amount of actual, real buyers, which drives the number of sales lower and lower.

On top of that, exchanges and publishers typically hate these kinds of buyers, because the error rates are so high, and the constant selling and reselling slows down pages and loses good publishers money. The best publishers are vigilant about this type of thing, and if they see fill rates go down, they’ll yell at their SSPs, which will in turn tell arbitrageurs to go away. Ask any arbitrageur, and their biggest roadblock is a lack of inventory that’s willing to take on this kind of low-fill demand, which is a lot like the wolves complaining that there aren’t enough hens around.

That’s my polite way of saying don’t try this at home.

Continue reading–you can find Part II of this two-part series through this link.